Solutions and Trade-Offs

At Influitive every month we get 2 ‘investment days’. During these days we are not bound to do planned work and are encouraged to invest in our professional growth. Usually developers will use up this time to learn new technologies, work on side projects, write blogs etc.

This time around I have decided to analyze the runtime and space complexity for different solutions to the problem: Given a string, verify whether all its characters are unique?. Despite it’s simplicity the algorithms we are analyzing are full of subtleties and interesting details worth looking at.

The benchmarks reported were calculated by running each solution 1,000 times with inputs of different lengths: 10, 100, 500, 1000, 2000, 10,000, 20,000 and 40,000 characters. The strings always contained unique characters and the time recorded was the elapsed real time. The object memory size was calculated using ruby’s Object.memsize_of(object) for the input of 40,000 characters.

Brute Force

We can start with the most naive (brute force) solution which involve checking every single character against the rest of the string.

def unique_brute_force(s)

s.each_char.with_index do |char1, i|

s2 = s[i+1..-1]

s2.each_char do |char2|

return false if char1 == char2

end

end

return true

end

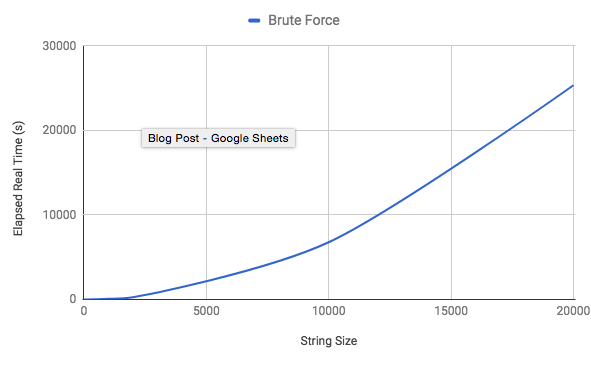

Despite its simplicity the shortcomings of this approach are apparent. The nested loops brings the runtime up to O(N²). We can corroborate by looking at the chart below:

Using a Hash

We do not need to compare every character against each other if we can keep track and check what characters we’ve seen so far. This can be easily achieved using a hash

def unique_with_hash(s)

characters = {}

s.each_char do |char|

return false if characters[char]

characters[char] = true

end

return true

end

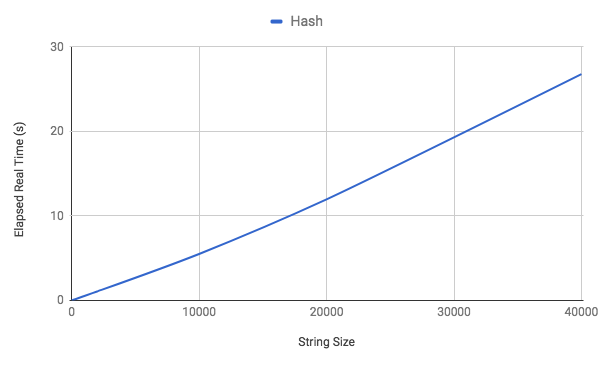

The algorithm runtime is very close to O(N) as we can see in the plot below:

This approach is clearly better than the brute force solution. We were able to complete the 40,000 characters run in a matter of seconds. In the worse case scenario this solution will require a hash of the full size of the string, which puts its space complexity at O(N). Our 40,000 characters hash reported a size of approximately 2,000,000 bytes.

Nevertheless, hashes are not simple data structures and they look up time is not always O(1) as we normally assume. To understand why we need to take a look at ruby’s hash implementation.

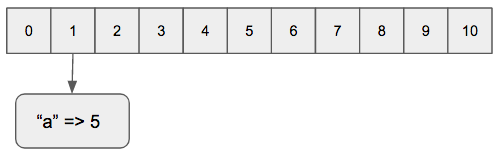

For a small hashes ruby creates an array and stores the key value pairs in order of insertion directly into it. When the size of the hash reaches 7, ruby discards this array, creates an array of size 11, then it proceeds to store the hash values the following way:

-

The keys will be hashed into a number using the murmur hash function. For example for a hash containing “a” => 5 , “a”.hash = 309038326836704191

-

The remainder between the hashed key and the current size of the array, which in this case is 11, is calculated to obtained the index where the values are to be stored, e.g 309038326836704191 % 11 = 1

-

Finally, the corresponding key => value pair is stored in the array.

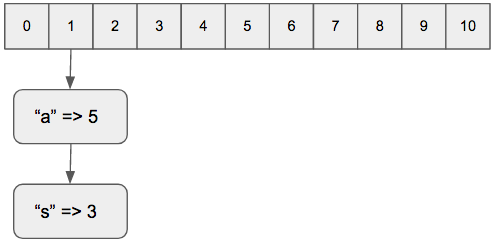

It is important to note that this procedure can yield repeated indexes for different keys. For instance, in our previous example the keys “a” and “s” both result in the index 1. Ruby handles this collisions by creating a link list inside each slot and appending the latest values at the end of the list.

When the density of collided values per slot reaches about 5, ruby increases the size of the array by an specific amount (11 -> 19 -> 37…), rehashes all the keys and re-stores the pairs. Source

This whole process has some important implications for our particular problem:

-

Ruby requires extra effort to hash the hash keys.

-

What on the surface seemed to be a look up time of O(1) is not quite so because we have to account for the extra time consumed by the iterations through the link list of collided values in a slot.

-

Also additional effort is required for the array resizing and key rehashing when the collision density reaches 5 at the different size thresholds.

-

Finally, additional memory is required for the linked list to store references to consequent values.

-

In terms of space complexity this algorithm is O(N). For our particular setup a hash with 40,000 elements takes up approximately 2,000,000 bytes.

In terms of space complexity this algorithm is O(N). For our particular setup a hash with 40,000 elements takes up approximately 2,000,000 bytes.

Using an Array

But we do not necessarily need to use a hash, when we see a character for the first time we can store a boolean in a array using its corresponding unicode as index, as our solution shows below:

def unique_with_array(s)

char_set = Array.new

s.each_char do |char|

code = char.ord

return false if char_set[code]

char_set[code] = true

end

return true

end

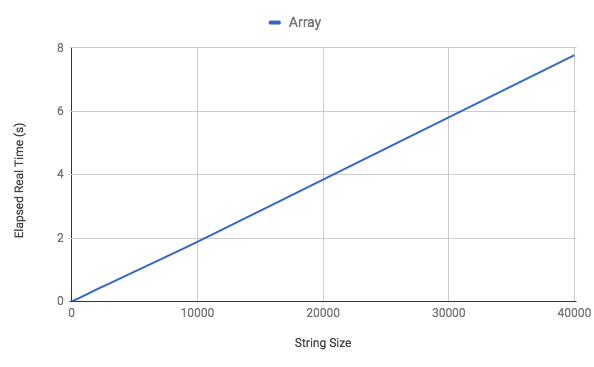

This solution also runs in O(N) but does not have to deal with the intricacies of the hash inner workings resulting in faster runtimes as we can see below.

The run with larger input (40,000 characters) runs almost 4 times faster than the hash solution!

The space complexity for this solution is also O(N) but the space occupied by the array is also considerable smaller than the hash with approximately 320,000 bytes for an array of 40,000 boolean values.

Bit Vector Approach

We can reduce our memory usage if we store our string using a Ruby’s Bignum.

The core of our previous solution relies on saving booleans at specific positions. We can achieve the same result by using a bit vector. The idea is to “flip” a bit for each character seen at their corresponding Unicode. For example if we’ve already seen the characters with Unicode codes 3 and 4 we would get the a vector representation of “11000”. Note how true values are now represented by “1” and the indexing starts from right to left.

If we want to see whether the character with Unicode 5 is in the vector already we just need to:

-

Create a vector that contains a “1” shifted 5 places (“100000”) which is achieved using the bit wise shift operator (1 « 5)

-

Then we just need to “&” the shifted value with the existing vector: vector & (1 « 5). The operation would look something like this:

100000 -> shifted value result of (1 << 5)

11000 -> characters with code 3 and 4 have been seen already.

______

000000 = 0

Since 5 had not been registered the result of the “&” operation is zero. Now we just need to update the value of vector to mark 5 as seen. We can do that by using the bit wise “|” operator: vector |= (1 « 5). This the equivalent of doing this:

1) Performing the "|" operation

100000

11000

______

111000

2) Assinging the result to vector

vector = 111000

Putting everything together we come up with the following algorithm:

def unique_with_bit_array(s)

vector = 0

s.each_char do |char|

code = char.ord

if (vector & (1 << code)) > 0

return false

end

vector |= (1 << code)

end

return true

end

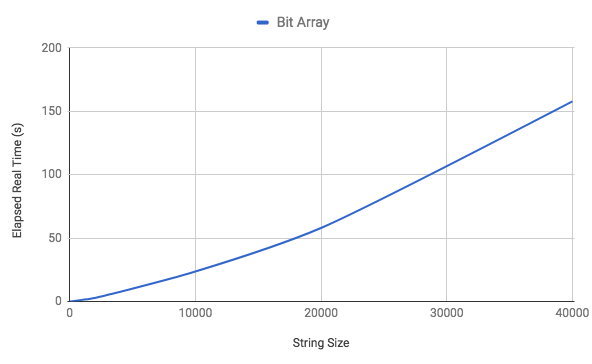

This algorithm runs in O(N) and it’s benchmark is shown below:

This solution is visibly worse than our previous ones (except brute force), which indicate that there is a price to pay when performing the bitwise operation over relatively big bit vectors. Nevertheless we have enormously reduced space complexity which now sits on O(1) since we only need a Bignum for storage. This is corroborated with our empiric space benchmark that results in a mere 5,040 bytes for the worse case scenario at the largest input.

Web Developer Approach

Finally, if we needed to implement this solution as web dev we probably would come up with something like this:

def unique_web_developer(s)

s.split("").uniq.length == s.length

end

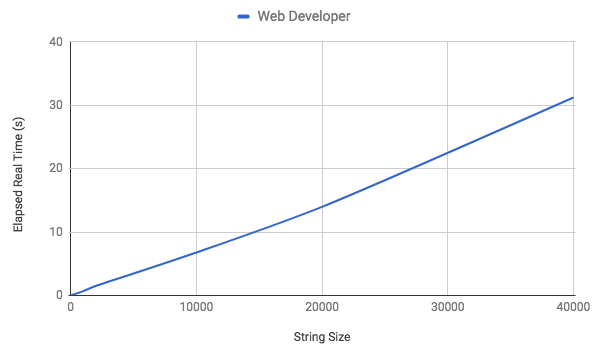

This solution is also O(N) since we basically iterating over the collection of characters twice, once to split it and once to uniq them. The runtime chart corroborates this:

The solution is quite satisfactory and is comparable with the hash solution but it’s still an order or magnitude higher than the array’s. In terms of space ruby instantiates 1 array after each operation (split, uniq) so we could probably assume that we’ll require 2 arrays in total space which would put its benchmark in approximately 640,000 bytes.

Summary

As usual the “best” solution for our use case will entirely depend on what we are optimizing for.

In terms of performance two solutions stood out: The array solution crushed the runtime benchmark completing our largest run in about 8 seconds. On the other hand, our bitmap solution, although considerable slower, was able to store the entire map in about 5,000 bytes.

Finally, if we were to optimize for readability and speed of development, we would probably go with the web dev solution, which offered a good performance trade off in exchange for simplicity. Thanks for reading!

NOTE: This article was originally posted here