Bits, Gates & Algebra

This starts a series of posts where I talked about the very fundamentals of computer architecture. These post are mostly based on my recent learnings from a couple of resources, namely But How Do It Know?, nand2tetris and Understanding the Digital World. All these are great starting points to learn how computers work from the very ground up. They assume no particular background whatsoever so they are a very good read for anybody interested in the topic, be sure to check them out!

10,000-foot view

On a (very) high level computers have 2 main components: the Central Processing Unit (CPU) and the Random Access Memory (RAM). The CPU can be seen as the the brain of the machine and its main functions are to perform calculations and control the flow of information across the whole system. RAM on the other hand, is the physical space where most actively used information is stored. These 2 devices work in tandem in a never-ending cycle as we can see below:

The CPU performs calculations using a set of data and instructions that are stored and fetched from the RAM. Based on the results of the calculations the CPU requests a new set of data and instructions which the RAM will again provide, repeating the never ending cycle.

Thus, a great part of understanding how computers work its about understanding how these two components interact with each other and how do they accomplish what they need to do. In the case of the CPU that is, how the data is processed and managed, while for the RAM how the data is stored and retrieved efficiently.

This makes sense intuitively if you think about the last time you bought a computer. When we buy computers we normally take a look at 2 key metrics: the processing power, generally measured on GHz, and memory capacity, measured on GBs. Higher processing GHz means the CPU is able to do more calculations per unit of time, while more GBs for storage translate into more RAM space for the computer to hold information at any given point.

The following series of posts will take a look at how these devices work and interact with each other. We’ll be starting our journey from the most fundamental unit of all: the bit.

Its CODES all the way down

On a (very) low level computers are dumb machines that are able to perform simple calculations and procedures fast, like almost light speed fast. When enough of these procedures are put together in the right sequence computers are able to perform tasks that are useful and seemingly complex to humans. They do all this by controlling the electrical current that runs through some small wires known as bits. At any given moment these bits can live in any of these two states:

- 1 (or ON) when electricity runs through.

- 0 (or OFF) when NO electricity runs through.

These bits can be arranged into sequences to express any arbitrary meaning or code we want to attribute to them. For example with a single bit, we can determine whether or not a lamp should be on or off. Our code could be something like this:

| Bit state | Lamp light |

|---|---|

| 1 | On |

| 0 | Off |

Now, with 2 bits we can do more interesting stuff such as determining what light should be on a traffic light. A code for this could look like the following:

| Bits state | Traffic Light |

|---|---|

| 00 | ❤️ |

| 01 | 💛 |

| 10 | 💚 |

| 11 | ⬅️ |

NOTE: Apologies for the heart emojis but apparently colored circle emojis are not a thing just yet.

Notice how we were able to encode 4 different states by only using 2 bits, this is because the order of the bits matter to the code we just created. In fact, as we add bits the possible amount of combinations double for every bit added. Thus, 3 bits will translate to 8 combinations, 4 to 16 combinations, and so on. The total number of combination can then be calculated by 2number_of_bits.

Now, Is there anything interesting, besides lamps and traffic lights, that can be encoded with bits? Yes lots of things! For instance with 8 bits, and its corresponding 256 combinations you have enough possible combinations to represent the whole latin alphabet, which usually consist of 26-30 characters depending on the language. In fact you even have some outstanding combinations to represent the capitalized version of each letter, numbers, punctuation symbols and some other weird characters. This exact same code exists already and it is known as ASCII.

This is a very useful code and it’s probably used by all computers nowadays but it’s important to understand that, just like our lamp or traffic light code, this is a man-made construct. A convention established by a group of people in a room that one day arbitrarily decided that computers should understand “01100011” as the character “c”. There is nothing intrinsically special about the bit combination “01100011” that enforces the meaning “c” on a particular computer. It’s just part of a standard agreed upon, most likely to have a consistent representation for the letter “c” across all computers, and devices regardless of their manufacturer.

Logic Gates

This thing about arbitrary codes is all well and good, but how do you go from bit combinations to full fledged systems capable of calculating and remembering things? It’s quite the journey but it all starts with logic gates. Logic gates are hardware devices that operate on bits and they usually have the ability to produce output bit(s) given some input bit(s). A couple of very simple gates are

Both of these gates operate on 2 input bits (a, b) and have 1 output (out). In the case of the AND gate out will only be 1 when both of the inputs a and b are 1. The OR gate on the other hand, produces a 1 outbit if any of its inputs a or b are 1. If you’re are a programmer it’s easy to draw parallelism between these gates and the common logic “and” and “or” statements used on your day to day job.

There’s another gate that’s worth taking a look at, the NAND gate. As its name implies the NAND gate is the negation of the AND gate. All it’s outputs on the truth table are inverted with respect to the “AND” gate. That is out is 1 for all combinations of inputs except for when both a and b are 1. Here’s the truth table for it:

One interesting property about the NAND gate is that it can be combined and arranged to create multiple other types of gates. For instance we can start by creating a NOT gate that is a gate that takes an single input a and produces the opposite output out by simply feeding the same input twice to the NAND gate.

We can use this result to recreate the previously seen AND and OR gates, as seen in the diagram below:

You can in fact extrapolate this idea and create ALL (yes ALL!) the different gates and devices you’ll ever need to build a computer only starting out from NAND gates! But in order to understand this we need to understand what the canonical representation of a boolean function is.

Canonical Representation

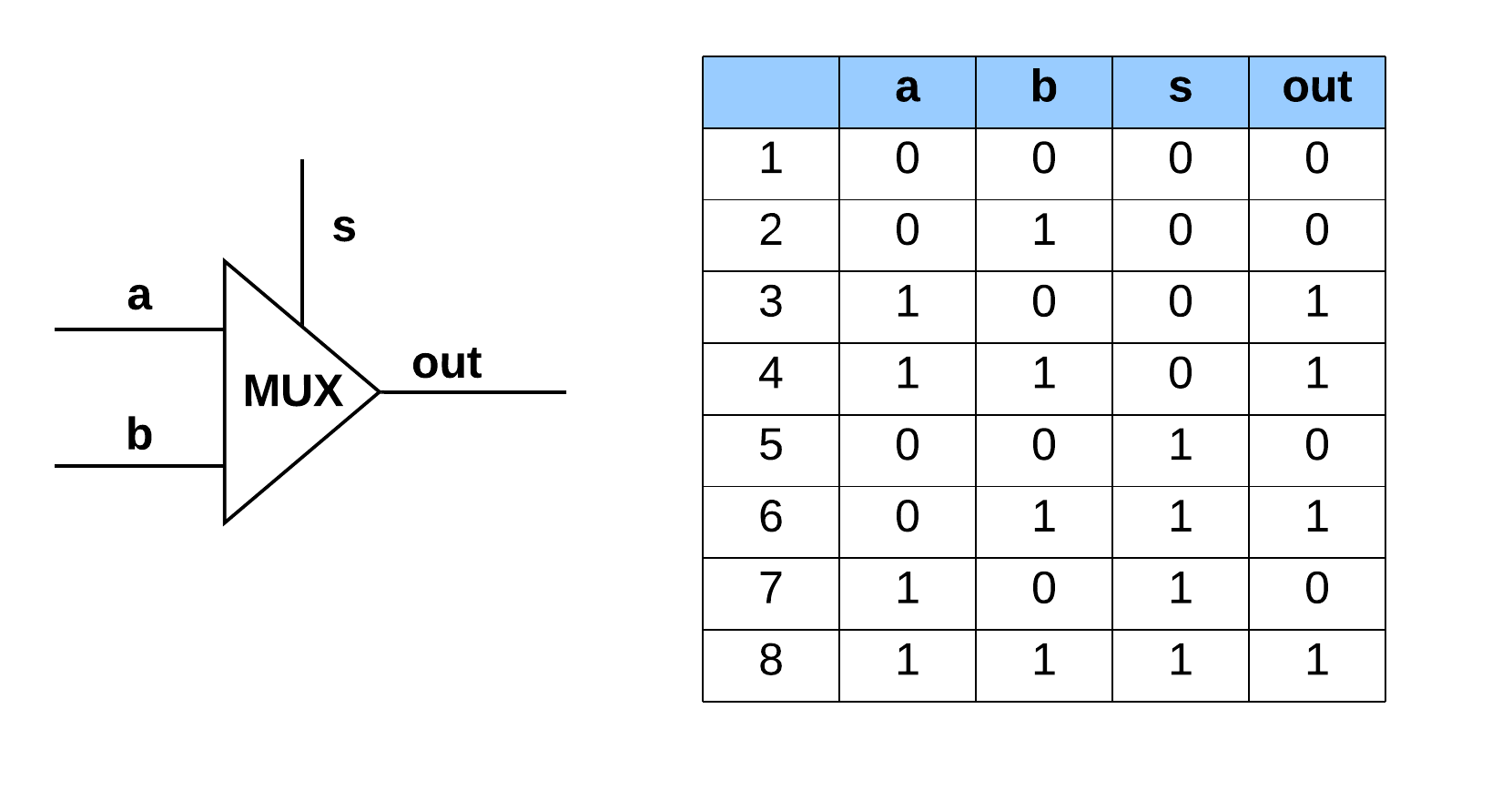

As we advance in our journey we’ll want to build more complex logical devices that fulfill different purposes. One of such is known as multiplexer and it is described below:

The multiplexer has 3 inputs and 1 output. It works in such a way that the input s determines which of the other inputs, a or b, becomes the output. So in this case when s = 0, out will take the current value of a. Conversely, if s = 1 the value of out will be set to the current value of b.

As circuits and devices become more complex it becomes much easier to study them using algebraic expressions. One straight forward way to derive such equations is by obtaining its canonical representation which can be done by using these steps:

- Select all the rows from the truth table where the output is 1

- “AND” all the inputs per row

- “OR” all the results from the step 2

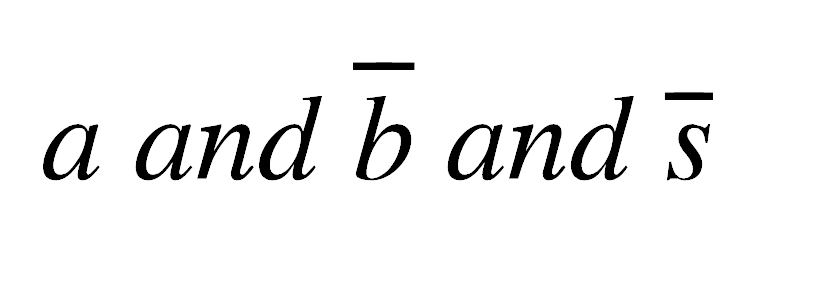

Let’s apply these to the MUX device we described above. From step 1 we know that we’ll be working with rows 3, 4, 6 and 8 since those are the bits combination that produce out = 1. We can take row 3 for example and express it in the following way:

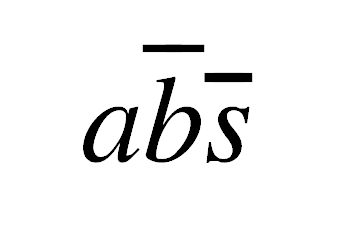

Notice how every input that had a value of 1 was expressed with the same letter found in the table, in this case a, and every input that had a value of 0 was drawn with a horizontal bar on top indicating that the input needs to be NOTed for the expression to work, in this case b and s. We can further simply the notation by removing the and altogether much like we do with regular equations when factors multiply, e.g. E = mc2:

Finally, applying step 2) to the outstanding selected rows 4, 6 and 8 and applying step 3) to all the corresponding results we obtain:

Notice how I’ve used + sings instead of explicit ors, again this is done to improve readability and to obtain a more equation looking expression which will become very convenient as we’ll see in the next section. We can easily verify that our equation conforms with the truth table by testing some cases. For example by substituting the values in row 4 a = 1, b = 1, s = 0 we get: 0 OR 1 OR 0 OR 0 which correctly evaluate to out = 1, feel free to test other rows to convince yourself.

One important result of the canonical expression is that it shows how we can potentially build any logical device by just using AND, OR and NOT gates which as explained above can all be constructed starting from NAND gates. This explains why NAND gates are normally use as the fundamental primitive to build all computers.

Boolean Algebra

We could construct a multiplexer device straight out of the canonical expression derived above but that would be a bit more complicated than necessary since we can simplify this expression using some boolean algebraic rules as shown below:

We can see that the resulting expression has been considerably reduced and will translate into simpler chip

In practice simplified chips are very desirable because they are cheaper to manufacture as they require less pieces, and occupy less space which is vital for today’s computer standards. It’s beautiful to see how a seemingly pure theoretical area, such as boolean algebra, can have a very real practical impact in the design of something so ubiquitous such as a computer.

Thanks for reading. Until the next time!