CPU

This continues the series on computer fundamentals I’ve been working on. In the previous entries we talked about logic gates and RAM today we’ll be exploring some of the main CPU components but we’ll start by doing a little introduction on how programs get translated into machine language that then can be processed by the CPU. This will also be a nice segue into future posts about compilers.

Programs

Programs are a series of steps that tell computers what to do. Nowadays, most programs are written in “higher” level programming languages that somewhat resemble human readable languages. For instance the program below adds prints the number from 1 to 100 in the ruby programming language:

for i in 1..100

puts i

end

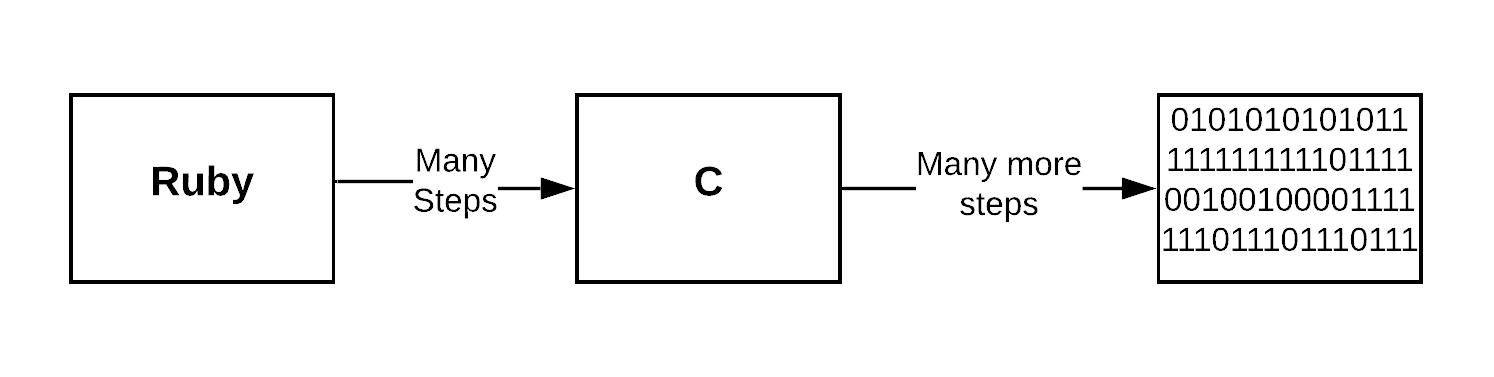

Nevertheless, as we’ve seen in previous posts computers are only able to encode and understand binary information so before these programs can be stored and executed they need to be translated to binary code, such translation is known as compilation. The process of compilation happens in many steps and varies considerably from language to language but in the particular case of Ruby goes like this:

In the example above ruby, a interpreted higher level language, gets compiled down to C which is a lot more performant but generally regarded as less expressive and harder to use for the lay programmer. C, on the other hand, gets compiled to assembly which ultimately gets translated to binary code (0(s) and 1(s)) by a program known as a assembler. The compiled program can then be loaded into RAM where is accessible to the CPU which ultimately executes it one instruction at a time, as seen in the diagram below:

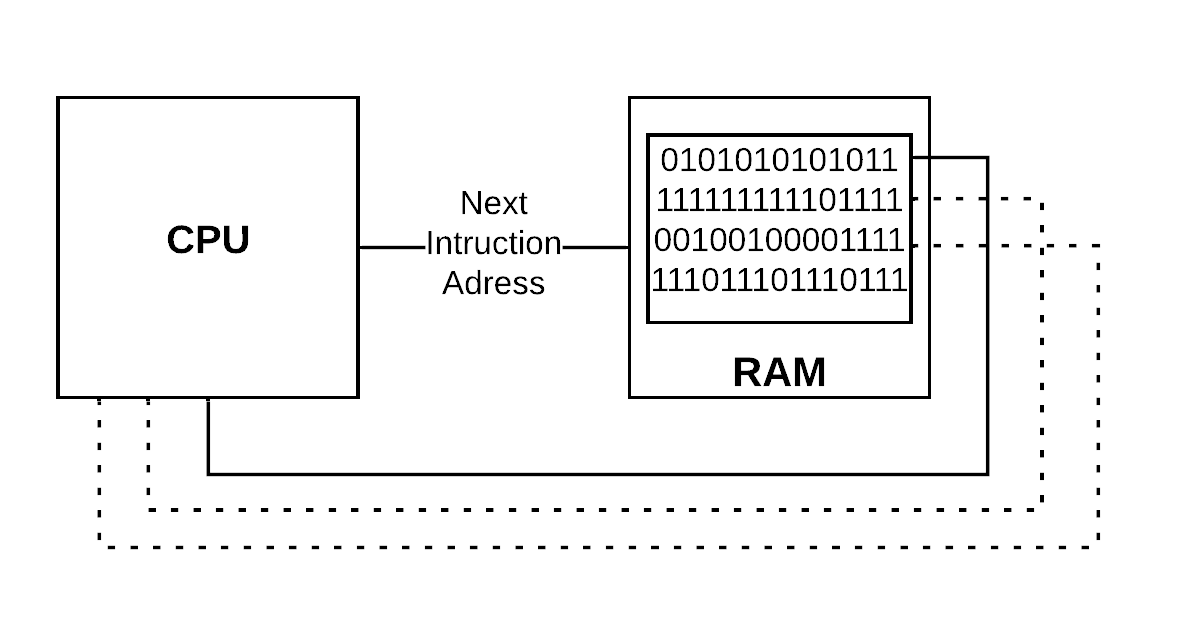

The CPU and RAM live in this perpetual fetch/execute cycle. Once the program is loaded in RAM the CPU can start fetching instructions and data. Some instructions will prompt the CPU to perform calculations on the data acquired so far. Some of the results from these calculation can then be used to determine the address of the next instruction to be executed and then the cycle repeats. This setup, where we have a distinct processing unit (CPU) and a storage device (RAM) for data and instructions is what we know today as the von Neumann Architecture. In this post we’ll take a closer look at the CPU and its main components.

Computer Architecture

Before we dig deeper into the CPU it’s worth while talking about the concept of computer architecture. While all computers work more or less in the same way their specific design philosophies and details vary significantly form provider to provider. This might be because different people have different ideas on what’s the best way to do things, but also because sometimes computers need to fulfill completely different purposes. For example desktop gaming computers are built to maximize performance with little to none concern about energy expenditure, while phone computers need to be more conservative about energy usage if they want to last a full day of charge. The specific layout and trade-offs used to design a computer is what its known as computer architecture.

Each architecture will have different strategies to achieve its goals, for example some will have 32 bit buses while others 64 bit, some will have more registers than others, some will want to have minimalistic ALU while others will try to jam as much functionality into the ALUs to max performance, and so on. An important practical consequence of these differences is that each architecture will have it’s own particular machine language otherwise know as assembly language.

Just like human languages, not all assembly languages are created equal. They are a reflection of the design decision used in the computer and programmers have to account for these differences when writing compilers for their higher level languages. This is why a program compiled for a particular architecture say a 32-bit CPU won’t work on a 64-bit machine the same way a Nintendo game wouldn’t just work if we download it into a PS4. With all this said we’re now ready to look deeper into the CPU.

CAUTION: The particular architecture I’m going to be showing in this post is a super-simplified and rather fictitious version of a CPU. It is not meant to show a fully functional computer but to make it easier to explain and understand how a CPU works at a higher level. So proceed at your own risk 😛.

CPU

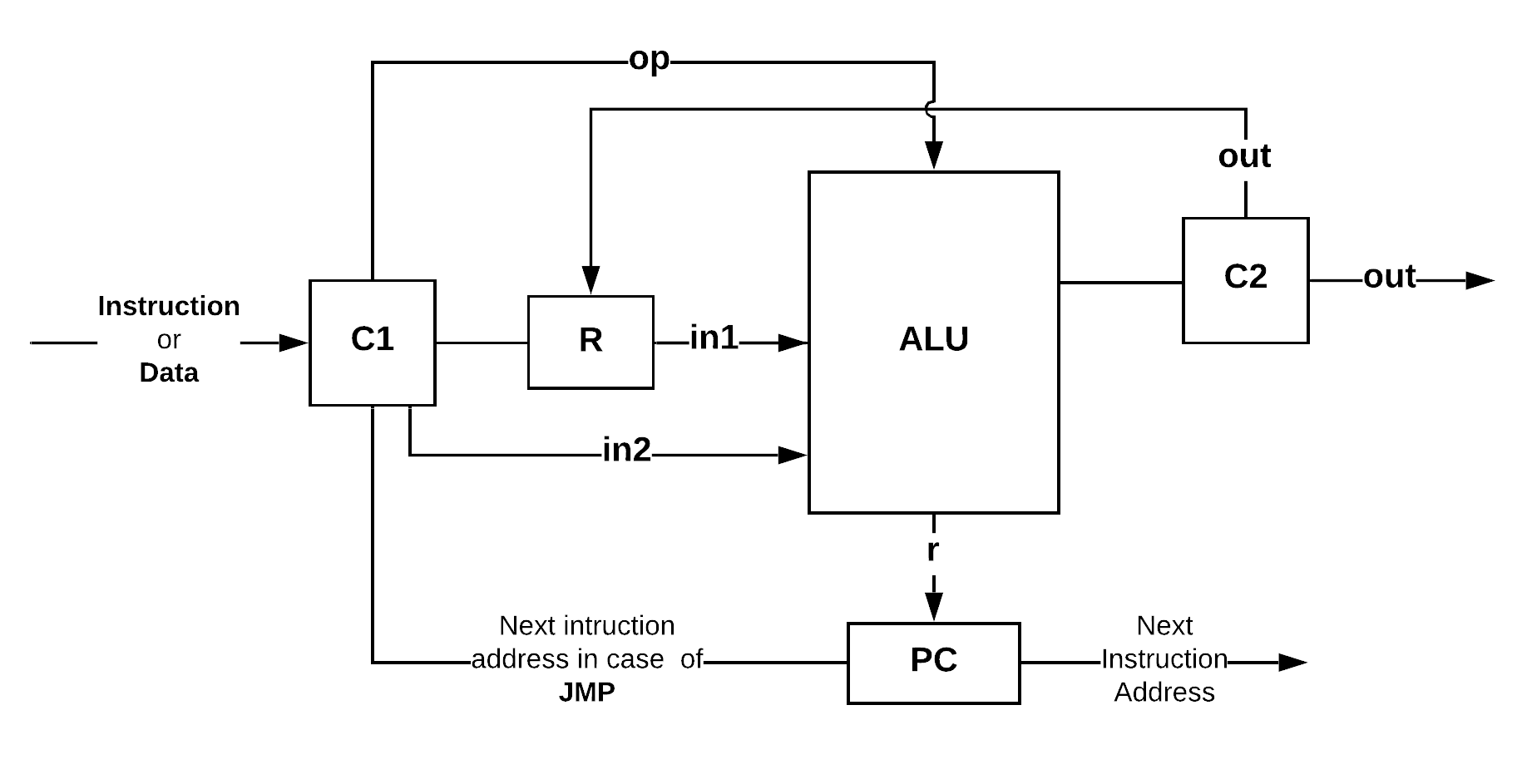

In the diagram below I’ve opened up the CPU box so that we can expose some of its main components:

This particular CPU consists of 3 different devices: the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU), a register (R) and the Program Counter (PC). There are also some “C” (for control) units which I use to represent some devices that help parse information and determine its flow across the whole system. On a higher level these components operate more or less like this:

The fist thing that happens is that the CPU receives some information from RAM, generally speaking this information can be either data or some program instructions which can also come in different types. The CPU should be smart enough to properly parse and reroute all type of information to the right place and that’s exactly what C1 does.

When the information fetched from RAM is data it can be either stored in R or it can be directly fed to the ALU. The ALU will then perform a specific calculation on its in1 and in2 inputs and will produce another data bus that can be stored back into R or RAM or both, C2 manages this decision. Finally, the PC determines the address of the next instruction or data to be fetched from RAM, by default the PC will just produce the address of the next sequential instruction, but because programs are generally not fully linear but have branches and loops the PC must rely on information obtained on the current cycle to determine what the next instructions should be. These extra bits of information are provided by the ALU and fed to the PC through r.

ALU

Our ALU performs operations on in1 and in2 which come from R and from RAM respectively. The specific operation to be performed should be specified on the currently running instruction and its fed to the ALU through op. Every op bit pattern maps to a particular operation we want to perform on the inputs, examples of those could be:

| Instruction | Result |

|---|---|

| 101010 | 0 (always returns 0 regardless of inputs) |

| 111111 | 1 (always returns 1 regardless of inputs) |

| 000001 | in1 + in2 |

| 010011 | in1 - in2 |

| ….. | ….. |

The main ALU output is out which corresponds to a bus containing the result of the operation. out can be stored back into R as a temporary value to be used on a subsequent operation, or it can be sent to RAM for future reference or it can be stored in both. The fate of out should be specified on the currently running instruction as well. The ALU also has some additional output that help inform other parts of the CPU about whether out is positive, negative or zero. These bits are represented by r and in our case are directly fed into the PC to help determine what the next instruction address is.

Registers

I talked in detail about registers on a previous post but mostly under the context of RAM. CPU registers are conceptually no different from RAM registers but contrary to RAM’s their purpose is to hold onto intermediary results that can be directly fed into the ALU. By storing these values in the near vicinity we prevent full round trips to RAM which translates into shorter computing cycles. Our computer contains one register R and as we’ve seen before the register can hold some results obtained by the ALU or information coming directly from RAM.

PC

The PC job is to determine the address of the next instruction to be fetched from RAM. Programs are supposed to be run sequentially one instruction at a time thus, it makes sense to store them in the order they are going to be run. Initially, the PC produces the RAM address of the first instruction, then after every cycle by default it will add “1” to the current address to fetch the next sequential instruction. This default behavior alone suffice for simple linear programs, but in reality programs have multiple branches and loops so the PC has also to be able to JUMP to a particular instruction if a particular condition is met, this is where the ALU output r comes into play. The PC uses r along with other information encoded in the current instruction to determine if the CPU should jump and fetch a particular instruction or if it should just fetch next sequential one.

Uff, well that’s all I got for you today. While I’ll admit I’m glossing over a lot of details I hope this helped you better your understanding on how the CPU operates. Happy coding!